Summary judgment for defendant

- A defendant may, at any time after filing a notice of intention to defend, apply to the court under this part for judgment against a plaintiff.

- If the court is satisfied that:

- The plaintiff has no real prospect of succeeding on all or a part of the plaintiff’s claim; and

- There is no need for a trial of the claim or the part of the claim;

The court may give judgment for the defendant against the plaintiff for all or the part of the plaintiff’s claim and may make any other order the court considers appropriate.

If the Plaintiff’s Statement of Claim does not disclose a cause of action it will be bound to fail, and the Defendant would be able to apply for Summary Judgment under Uniform Civil Procedure Rule 293.

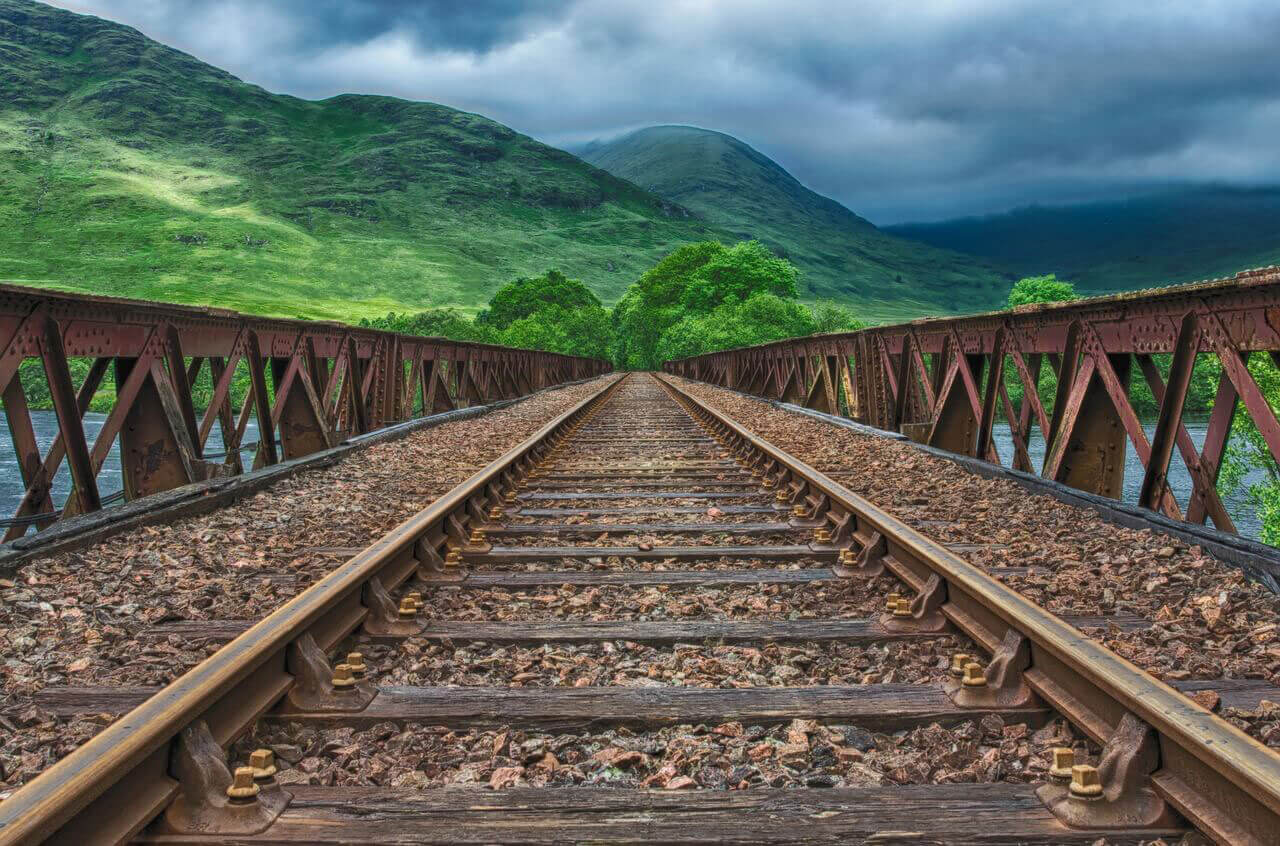

Summary of General Steel Industries Inc v Commissioner for Railways (NSW) (1964)

This case details the Court’s authority to consider the issue of cause of action and whether or not the company, General Steel Industries, had a cause of action when it commenced proceedings against a State authority, Commissioner for Railways (NSW) after it began to use General Steel Industries’ invention.

Facts in General Steel Industries Inc v Commissioner for Railways (NSW) (1964)

General Steel Industries held letters patent with respect to an invention titled ‘Railway Vehicle Body and Truck Central Bearing’. General Steel Industries contracted the Commissioner for Railways (NSW) and two other Defendants for the assembly and manufacturing of central bearing structures for the State railway system. However, shortly after the agreement, General Steel Industries believed that Commissioner for Railways and two other Defendants were breaching its patent and brought an action in the High Court restraining the Defendants from infringing its patent. All three Defendants answered the Statement of Claim, by invoking the Patents Act 1952 (Cth) specifically sections 125 and 132 which provided a Crown exception to patent infringement and argued that the claim should be summarily dismissed.

Held

The High Court agreed that the case be summarily dismissed on the grounds that the Defendants’ actions, as the Crown and contracted to the Crown, were exceptions to infringement in sections 125 and 132 of the Patents Act 1952 (Cth) and that therefore the Statement of Claim disclosed no cause of action that could succeed.

The Chief Justice at [135] stated that he was ‘convinced to the requisite degree that the Commissioner’s act in relation to the invention for which the plaintiff holds letters patent and of which the Plaintiff complains are covered by section 125 aided by s 132, and that the plaintiff’s actions for infringement is precluded by s 125(8)’.

Key statements of General Steel Industries Inc v Commissioner for Railways (NSW)

The High Court in General Steel Industries Inc v Commissioner for Railways (NSW) (1964) stated that:

“The plaintiff rightly points out that the jurisdiction summarily to terminate an action is to be sparingly employed and is not to be used except in a clear case where the Court is satisfied that it has the requisite material and the necessary assistance from the parties to reach a definite and certain conclusion. I have examined the case law on the subject, to some of which I was referred in argument and to which I append a list of references. There is no need for me to discuss in any detail the various decisions, some of which were given in cases in which the inherent jurisdiction of a court was invoked and others in cases in which counterpart rules to Order 26, r. 18, were the suggested source of authority to deal summarily with the claim in question. It is sufficient for me to say that these cases uniformly adhere to the view that the plaintiff ought not to be denied access to the customary tribunal which deals with actions of the kind he brings, unless his lack of a cause of action – if that be the ground on which the court is invited, as in this case, to exercise its powers of summary dismissal – is clearly demonstrated. The test to be applied has been variously expressed; “so obviously untenable that it cannot possibly succeed”; “manifestly groundless”; “so manifestly faulty that it does not admit of argument”; “discloses a case which the Court is satisfied cannot succeed”; “under no possibility can there be a good cause of action”; “be manifest that to allow them” (the pleadings) “to stand would involve useless expense”.

Furthermore of the case the Court stated that:

“The railway system of the State is, in my opinion, undoubtedly a service of the State and the use of the invention in the construction of railway carriages to be used by the Commissioner in that railway system is a use for a service of the State or for the services of the State within the meaning of the expression in the Patents Act 1952, whichever may be the proper way to read the final words of s. 125(1). One could scarcely imagine that sections such as ss. 125 and 132, with their evident practical purpose, did not extend to include within the expression the use of the services of the Commonwealth or State, the use of an invention for the purposes of one of the Government railway systems in Australia.”

Furthermore of the case that Court stated that:

“All these factors combine, in my opinion, to require the answer that the Commissioner is an authority of the State within the meaning of ss. 125 and 132 of the Patents Act. I am also of opinion that the use by the Commissioner – if his contracting with the other defendants in the circumstances amounts to a use of the invention by him, as indeed the plaintiff claims – is a use for the services or for a service of the State, within the meaning of those sections. These conclusions are, in my opinion, of that clear and definite nature which is requisite if an order based on them is to be made denying the plaintiff a right further to proceed with its claim against the Commissioner”.

Key takeaways from General Steel Industries Inc v Commissioner for Railways (NSW)

Essentially, the case of General Steel Industries Inc v Commissioner for Railways (NSW) (1964) developed the common law threshold test for attaining summary judgement with a requirement that there be “no reasonable cause of action” and requiring the case to be “manifestly groundless”3 or “clearly untenable”. The impact of the threshold test has recently been supplemented by section 31A of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and section 25A of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) both of which legislate the principles found in General Steel Industries Inc v Commissioner for Railways.